Building from What's Already Working: On and Off the Mat

Most of us get into a pose and immediately scan for what's wrong. The hip isn't open enough. The hamstring is tight. The shoulder needs adjusting. We dismiss what's already stable and focus entirely on what's missing.

In This Article

- •What it means to build from existing strength — beyond "fixing what's broken," understanding how to anchor in what's already stable

- •How to practice this on the mat — specific approaches in poses that help you name what's working first

- •Where you dismiss stability in daily life — conversations, work, transitions where you jump straight to what needs fixing

- •Language for shifting the pattern — exact phrases for connecting physical foundations to life foundations

Introduction

Building from what's already working means finding the stable point first—the anchor—and letting everything else organize around it. Not ignoring what needs attention, but not starting there either.

This matters because when you lead with what's broken, you undermine the foundation you're standing on. You can't build a stable structure by constantly dismantling the base. The practice here is learning to name what's already strong, feel it in your body, and build from there.

This is NOT toxic positivity. It's not pretending limitations don't exist or forcing gratitude for things that genuinely aren't working. It's recognizing that stability already exists somewhere—even if it's just your breath—and that's a legitimate place to start.

On the Mat

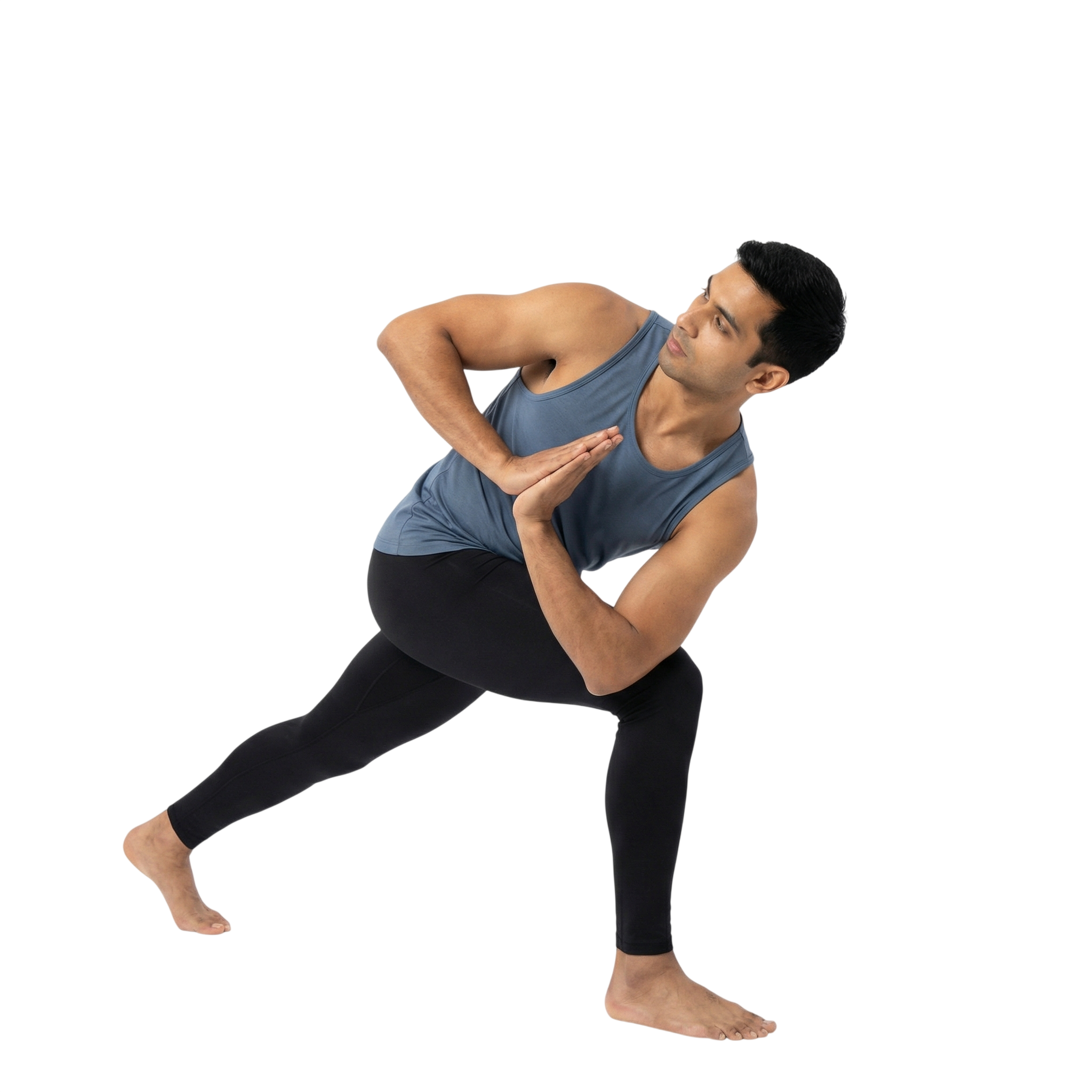

When you enter a pose, pause before adjusting anything. Take one full breath and name what feels strong. It might be your hands pressing into the earth in Downward Dog. It might be your front leg in a lunge. It might be the simple fact that you're breathing.

Say it internally: "My hands are stable. My breath is steady. My standing leg is strong." Make it specific. Feel it in your body. Then build from there. Let adjustments come from that place of existing stability rather than from a place of fixing inadequacy.

Pose selection & rationale: Use poses with clear bases—standing poses (Warrior I, Warrior II, Triangle), forward folds (Ragdoll, Seated Forward Fold), arm balances (Plank, Downward Dog), and balance poses (Tree, Warrior III). These require students to establish foundation before building complexity.

Key cueing language:

- "Before you adjust anything, name what's already stable."

- "What feels strong right now? Start there."

- "Your breath is working. Build everything around that."

- "Notice what's holding you first, then explore what wants to shift."

Sequencing/pacing approach: Start with foundational poses early in the sequence (simple lunges, Plank, Downward Dog) and return to them multiple times. Each time, cue students to find what's stable before building complexity. Move slowly enough that they have time to actually notice—don't rush the inquiry.

Common obstacle + teaching response: Students will default to fixing mode immediately. They'll enter the pose already adjusting. Your response: name what you see that's working. "Your front leg is strong. Feel that first." Give them permission to start with something small. If they can't find anything else, the breath always counts.

Off the Mat

The same pattern that shows up in poses appears everywhere—you just might not have named it yet.

At work: You finish a project and immediately move into what could have been better, what didn't work, what needs fixing next time. You skip right past what you executed well, what went smoothly, what actually worked. The debrief becomes a list of problems to solve rather than a foundation to build on.

In conversations: Someone shares something vulnerable and you jump straight to advice mode. You're already fixing before you've acknowledged what they did manage—the courage to speak, the self-awareness to recognize the pattern, the fact that they showed up to talk about it at all.

After work: You walk in the door and immediately scan for what needs doing. Dishes in the sink. Laundry unfolded. The email you forgot to send. You dismiss the fact that you made it through the day, that you're home, that you have space to rest. You don't anchor in what's already stable before adding the next task.

During transitions: You finish one thing and immediately jump to the next without pausing to register completion. No breath between. No acknowledgment that something ended before something else begins. You're building on a foundation you never actually felt.

In parenting or caregiving: Your kid does seven things right and one thing that needs correction. Guess which one you focus on. You're already planning how to address the problem before you've named what they're doing well. The foundation—their effort, their trying, their showing up—gets dismissed in favor of the fix.

What makes this hard

The pattern persists because our brains are wired for threat detection. Noticing what's wrong kept our ancestors alive. The problem now is that your nervous system treats a tight hamstring or an incomplete email with the same urgency it once reserved for actual danger. Fixing feels productive. Acknowledging what's working feels indulgent, like you're wasting time. It's not. You're establishing the base you're building on.

How to share examples: Pick 1-2 scenarios that match your students' lives. If you teach professionals, the work debrief example will land. If you teach parents, the parenting example resonates. Be specific—"You finish a project and immediately list what could have been better" is more useful than "We focus on the negative."

When to introduce off-mat material: Bring this in during transitions or at the end of class during savasana setup. Not in the middle of a challenging pose—wait until they have mental space to receive it. The bridge between mat and life works best when students aren't actively working hard physically.

Keep it invitational: Frame as curiosity. "If you notice this week where you skip what's working and jump straight to fixing..." Don't assign homework. Don't make it a should. Plant the seed and let them explore if they're curious. Some will, some won't. That's fine.

Making the Connection

Connecting your experience on the mat to your life off the mat.

"Bridge phrase 1: "The pattern on the mat—entering a pose and immediately scanning for what's wrong—shows up everywhere. You finish a conversation and replay what you should have said differently. You complete a task and move straight into the next one without pausing to register what you just did well. You're building on a foundation you never actually acknowledged. The practice isn't fixing less. It's feeling what's already stable first. Then building from there.""

"Bridge phrase 2: "When you get into Warrior II and your attention goes straight to the back knee or the front thigh, you're dismissing the feet that are holding you. Those feet are stable. That's real. That's not something you're making up or forcing yourself to feel grateful for. The same thing happens off the mat—you walk through your day dismissing what's already working in favor of what needs attention. This practice is about naming the foundation first. Not ignoring problems. Not pretending everything is fine. Just starting with what's actually holding you before you build on it.""

When to deliver: Use these phrases during transitions (moving from Downward Dog to standing, for example) or when setting up final savasana. Don't over-explain afterward—state it once, let it land, and move on. Students will make their own connections.

How to deliver: Keep your tone simple and matter-of-fact. You're pointing out a pattern, not giving a sermon. No drama, no performance. Just clear observation delivered like you're thinking out loud.

Keep it minimal: One bridge phrase per class is enough. More becomes lecture. The power is in the precision—say it once, say it clearly, and let students sit with it.

Try This

This week, try this: Before you jump into fixing mode—in a conversation, after completing a task, during a transition—name one thing that's already working.

You don't need to fix less or stop noticing problems. Just pause long enough to name the foundation first. "I showed up to this conversation." "I finished that email." "I'm breathing right now." Something specific, something real.

Pay attention to how it feels to start there. You might notice resistance—like you're wasting time or avoiding the real work. That's just the pattern trying to stay in place. The practice is the noticing, not achieving some enlightened state where you never focus on problems again.

How to offer this: Frame it as genuine option, not requirement. "If you're curious this week..." Works better than "This week, I want you to..." Most students won't do it, and that's completely fine. The ones who need it will experiment. The invitation itself has value—it names the pattern and makes it visible.

Want to explore building from what's already working in your practice? The "Building Foundations" class (Season 2, Episode 1) walks you through this concept in a 30-minute slow flow. Where do you notice yourself jumping straight to fixing mode—on the mat or off?